Ajax: a new approach to web applications

Jesse James Garrett

February 18, 2005

Translated by Denis Sureau on May 6, 2006.

If anything in the current design of the interaction can be called "elegant," it is the creation of web applications. After all, when was the last time you received praise for something related to the design of the interaction of a product that was not on the Web? (OK, except iPod.) All new, complex, innovative projects are online .

Despite this, web interaction designers cannot help but feel envious of our colleagues creating desktop software. Desktop applications are rich and responsive, which seem unattainable on the web. The same simplicity that allowed the network to spread quickly also creates a disconnect between the opportunities we can provide and the opportunities users can get from a desktop application.

The gap was closed. Just look at Google Suggest. Note how suggested terms are updated as you type almost instantly. Now look at Google Maps. Zoom in. Use the cursor to grab the map and move it a little. Again, everything happens almost instantly, without having to wait for the pages to reboot.

Google Suggest and Google Maps are two examples of a new approach for web applications that we at Adaptive Path have called Ajax. This name is short for Asynchronous JavaScript + XML and represents a fundamental advance in what becomes possible on the Internet.

Let's define Ajax

Ajax is not one technology. In fact, these are several technologies, each of which develops on its own and combines in a new way. Ajax includes:

- Standards-based representation using XHTML and CSS

- Dynamic display and interaction using the Document Object Model

- Data exchange and manipulation using XML and XSLT

- Asynchronous data retrieval using XMLHttpRequest and

- JavaScript for their joint implementation.

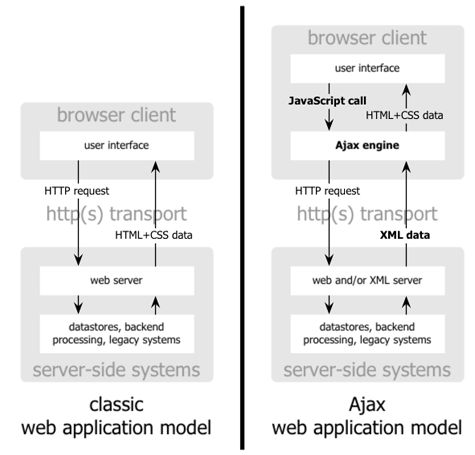

The classic web application model works like this: Most user actions in the interface trigger an HTTP request to the web server. The server does some processing - extracting data, crunching numbers, communicating with various legacy systems - and then returning an HTML page to the client. This is a model suitable for the initial use of the Internet as a hypertext medium, but as fans of The Elements of User Experience (1) know, what makes the Internet good for hypertext does not necessarily make it good for software applications.

Fig. 1: Traditional model for web applications (left) versus Ajax model (right).

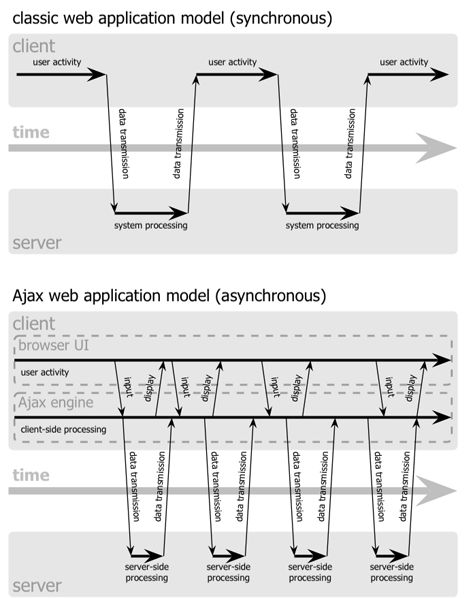

This approach shows a lot of technical things, but it does nothing good for the user. While the server is doing its job, what is the user doing? We see that there is expectation. And at each step of the task, something else awaits the user.

Obviously, if we were designing the Web from scratch for applications, we would not leave the user waiting. Once the interface is loaded, why does the user interaction stop every time the application Does the application need anything from the server? In fact, why would a user even see an application using a server?

Why Ajax is different

Ajax eliminates the start-stop-start-stop aspect of web interaction by entering an intermediary - the Ajax engine - between the user and the server. It may seem that adding a layer to an application will make it less responsive, but the opposite is true.

Instead of loading a web page at the beginning of a session, the browser loads the Ajax engine - written in JavaScript and usually wrapped in a web browser. in a hidden frame. The engine is responsible for both rendering the interface that the user sees and communicating with the server on behalf of the user. The Ajax engine allows the user to interact with the application asynchronously, regardless of communication with the server. Thus, the user never encounters an empty browser window and an hourglass icon while waiting because the server is doing something.

Figure 2: Synchronous interaction diagram in a traditional web application (top) versus asynchronous Ajax application schema (bottom).

Each user action that typically generates an HTTP request takes the form of a JavaScript call to the Ajax mechanism. Any response to a User Action that does not require a connection to the server - for example, simple data validation, editing data in memory, or even some navigation - is handled by the engine itself. If the engine needs something from the server before responding - if it submits data to the server, be it processing a request, loading additional interface code, or extracting new data, the engine makes some kind of request asynchronously, usually using XML, without blocking the user's interaction with the application.

Who uses Ajax?

Google is making significant investments in developing the Ajax approach. All the major products Google introduced last year - Orkut, Gmail, the latest beta of Google Groups, Google Suggest and Google Maps - are Ajax apps. (For more technical hacks on these Ajax implementations, try these excellent analyses of Gmail, Google Suggest, and Google Maps.) Others have followed suit: many of the features we love on Flickr depend on Ajax, and the A9.com research engine and Amazon use similar techniques.

These projects demonstrate that Ajax is not only a technical thing, but also practical in real applications. It's not another one of those technologies that only works in the lab. And Ajax apps can be any size, from the simplest, most unified Google Suggest feature to the most sophisticated and sophisticated Google Maps.

At Adaptive Path, we have been doing our own work at Ajax for the past few months, and we realize that we have only scratched the surface of the richness of interaction and performance that Ajax applications can provide. Ajax is an important development for web applications, and its importance is only growing. And since there are so many external developers who already know how to use these technologies, we expect many other organizations to follow Google's lead in gaining the competitive advantage that Ajax provides.

Let's go deeper

Biggest challenges when creating

The original document is licensed under the Creative Commons License. Some links have been replaced with links to francophone sites.

The license for this French translation is as follows: You may print this document and distribute it without restriction, provided that the author's name and all legal notices remain unchanged. You cannot publish this document to another website; instead, link it to this page.